Anger has never come easily to me. For a long time, I thought I was immune to anger and the need to express it. In the face of people treating me like shit, I had learned to weather the storm. Keep my cool, cool as a cucumber. Don’t react. I prided myself on being a guy who was never quick to anger, especially at other people for things they had done to me. I didn’t have a problem standing up for my friends, speaking out against some extreme display of social inequity, or telling drunk men off for being so obnoxious. Like a pit bull, protecting others comes naturally to me. But anger was the last emotion I felt when it came to my own problems. My anger always came out awkwardly, like some last-ditch Hail Mary pass toward some vague shape of justice right as the clock runs out.

I studied gender studies in college and knew the dark side of anger that haunted unhealed men both from an intellectual perspective and from a deeply personal one. My dad wasn’t an angry man, but he was the first in his family to break the generational curse of shitty dads. His father (bald, stoic, white shirt with sleeves rolled once) was a bona fide smoke-a-pack-a-day-armchair-alcoholic who never had nothing nice to say to nobody. Embarrassing in public and terrifying in private, my grandfather didn’t know how to love himself, so he took it out on everyone who tried to love him. The problem with masculinity is often not that men inherently hate women but that men inherently hate themselves, and anger becomes the only emotion they can express safely.

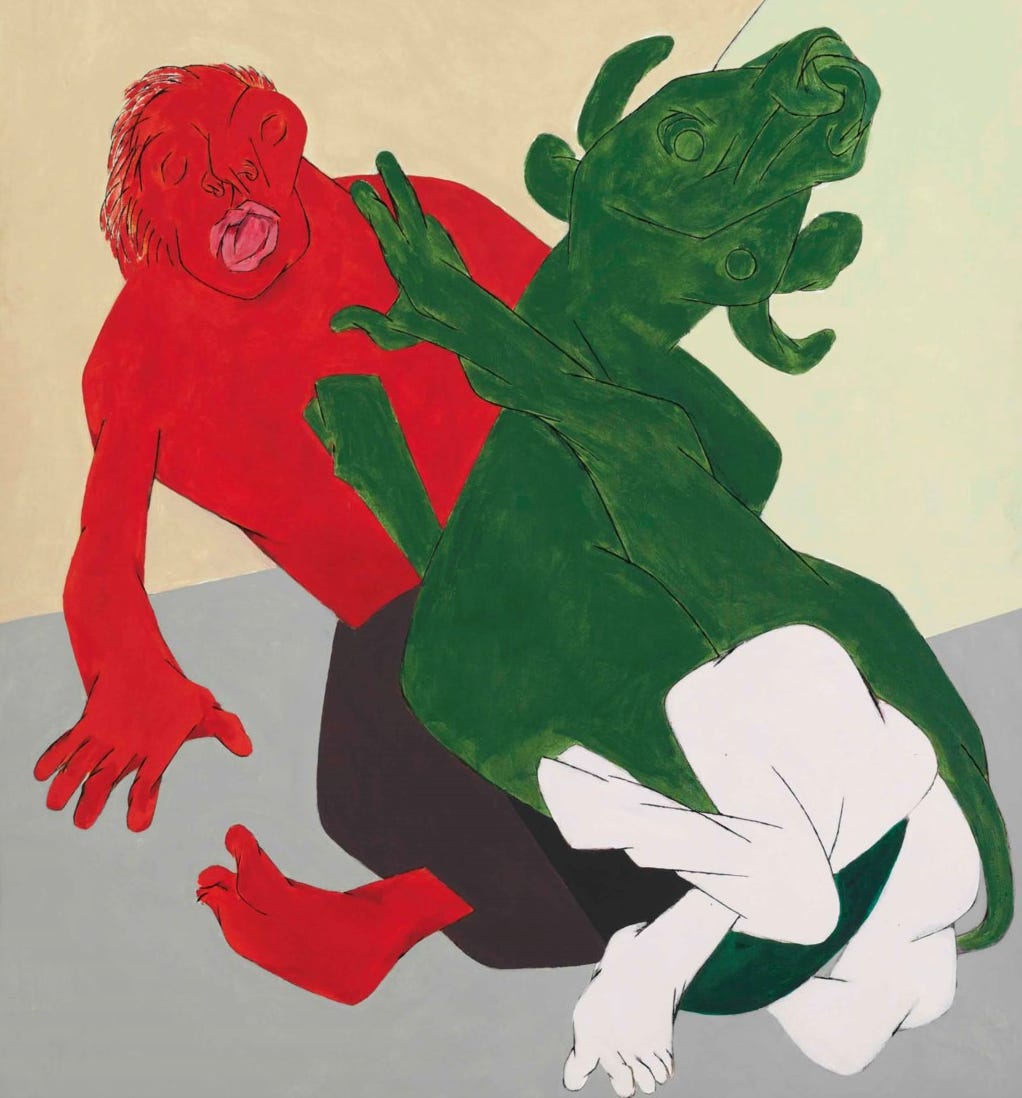

My dad swore he would never be like his dad, and he was right. He would hug us, kiss our cheeks wet, carry and cradle us in his arms from the car to our beds, scratch our backs until we fell asleep. He did all of that without a light to guide him, and I am so lucky to call him my dad. But cursebreaking is full of hauntings. It is the type of sorcery that takes a lifetime. Anger (like energy) cannot be created or destroyed—only converted from one form to another. Raw pain, deep grief, or gendered wounds don’t go away if you do not allow yourself to access them. There are no cheat codes for our emotions. Unmetabolized anger can get trapped like gas beneath the surface of the spirit. Any attempt at burial will not last. Without a regular pressure valve, it goes one of three ways. Inward. Sideways. Or, eventually, it comes up to the surface with enough force to blow up life as you know it.

My dad is a sideways kind of guy. He did the best he could without therapy, but he just doesn’t know himself very well. His pain is dormant most of the time. It goes unnoticed. Like alcoholism, masculinity can also be a family disease. Until the wound is properly healed—with care, comfort, and compassion, things boys are not inherently given—it will bring isolation, secrecy, guilt, and shame upon anyone whom it touches. Sometimes when my dad lashes out when he can’t find what he’s looking for in the garage, I have to remember that he is still that scared boy with a swollen lip in the bathroom looking for love from a father who washes his mouth out with soap instead.

Even though I didn’t grow up with a bad dad, I was still afraid of anger in masculine form. I knew well the biological falsehoods linking testosterone and anger, but I still couldn’t help but fear how the boogeyman of anger would show up in my life after transitioning. Before that, when people fucked with me, I’d started to fight back. Give them hell. Be the loud, angry feminist everyone loved to hate. I perfected the art of performing womanhood in ways that were hard to swallow (even for myself). But through the act of transitioning, I became acutely aware that anger, when coupled with masculinity, meant something entirely different. Flashes of violence. Fear. Dominance over others. I didn’t want a part in any of that, so I chose to opt out of anger entirely.

Like many other trans guys of my era, I had to wade through the muck of numerous outdated fears about masculinity to find my way back to myself. Early in my transition, I pledged to embody a different kind of masculinity. I’d be a chill guy. A good guy. Not like those other men out there— the men who are still secrets to themselves. I would listen to women and femmes and believe them when they told me about their experiences. I would take the torch that my dad lit and carry it into this darkness toward a softer, more gentle shape of manhood than the ones that came before us.

The only problem was that my whole relationship with masculinity became dependent on what people thought of me.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to BOYS LOVE POETRY to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.